What is a Faith Community?

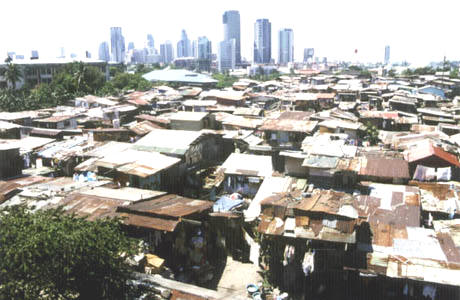

A Community of Hospitality is a cluster of committed people/place of love

and caring

for normal people (normal = look good on the outside but covering up pain, hurt,

damage, wound and sin on the inside) and

for the needy (needy= look damaged, and are open about the reality of the damage

and their desire for change).

It expresses the love of Jesus and the truth of Jesus in such a way

that the Holy Spirit transforms the normal and needy into Jesus-type people

who following confessional lifestyles or 12 step-type processes

passionately seek change in the structures and culture of the city

so the city reflects Jesus the Integrator of the Universe.

A Movement is a web of diverse-similar communities each serving different urban pockets

with shared values and interdependent and mutually accountable leadership.

Each community will develop an Urban Spirituality reflecting their

Lifestyle and Values

which in turn expand the Spirituality of the Centre and Hub.

What is an Emergent Faith Community?

The Quest for Structural Identity

If our aim is forming a new faith community, what do we mean by new faith community or church? This is a question of outcomes. It is a question of group structures within a movement momentum.

Listen to the public query and cry of the leader of a large organisation, standing on stage quietly reflecting on Jesus words, "Tear down this temple and in three days I will rebuild it." It is in Brazil, as we worship with leaders of forward action in the Rede Evangelica Nacional de Acao Social (The National Evangelical Network for Social Action). "The temple was torn down, it was gone. What did he rebuild? It was not a building but a movement of relationships. the building was gone, never to return."

You are the new temple of God, a network of apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastor-teachers and deacons. This is the new structure. Built on the apostles. But they are only the foundation. Following them are the care-givers, the mercy people, the healers...

The Reality of Simply Copying

If we are part of an existing church that is seeking to expand or of a mission that plants churches then that question has been answered by our leaders and we simply seek to reproduce the model we are part of. In other situations we tend to emulate the style of church we see around us that has arisen from within the culture.

If we are to create new movements of churches we need to return to our definitions, and evaluate emergent trends globally.

Jesus Formed A Mission Team not a Church

Jesus did not plant churches. He formed a mission team of disciples. Around them was a wider group of disciples. He did not define the nature of group structures they were to use to further raise up disciples.

Jesus did not train them in the cult ie religious ritual, ceremony, performance. In fact he spoke against such things as tending to become the centre of people's understanding of God when they were minor issues. The important issues were inner values, and relationships. But he did not negate the cultic issues of worship, attending the synagogue and occasionally singing a hymn, just reduced them down to minor details.

His mission team was a wandering training school of life character and preaching skills. They were close. They were community. they practiced a communal sharing of possessions. They were mobile. They were preachers involved in power encounters. They followed their leader.

Jesus only spoke twice about the church (on this rock I will build my church), and these were references probably back-interpreting the later context into the history.

Jesus Commissioned us to Go Make Disciples not Churches

Jesus did not command us to go plant churches. He spoke to a group of disciples whom he had discipled to go form groups of disciples, and by this to disciple the nations. The presumption is that they would use a similar methodology and structures.

His structures involved a leadership team, training in character and relationship, training in wide-scale proclamation, caring for the poor in the context of signs and wonders.

Discipling is Communal

Answer Yes/No. If Jesus command to disciple was to a small group, and if he had modelled it with a small group, then can we make disciples without small group dynamics?

Jesus Commissions us to Love, Love results in Community

True/False. If we love, then we seek to create communities of love. The multiplication of communities of love is a normative process for disciples.

Jesus Taught Truth from Action and Life

True/False The primary locus of teaching is as a group are involved in action together with a leader

True/False The primary locus of teaching is in reflection with a team as the leader goes about in public teaching

Emergent Faith Communities in Acts

There are three types of emergent faith community seen in Acts:

-

In addition we find Paul the apostle, and Jesus developing apostolic teams

* revival-based multi-ethnic mega-churches (Jerusalem, Antioch),* converted synagogues that continued with similar structures* city-wide networks of extended family huse churches.

All include:

- * Defined leadership structures

- * Birthed in evangelism and the work of the Holy Spirit

- * Preaching and teaching of the word

- * The Rituals of the Lord's Supper and Baptism

- * Extended family/small group meetings house to house

- * Larger group meetings weekly

- * Economic sharing

- * Some would say worship (I find it present but do not find it central in Jesus, or in Antioch).

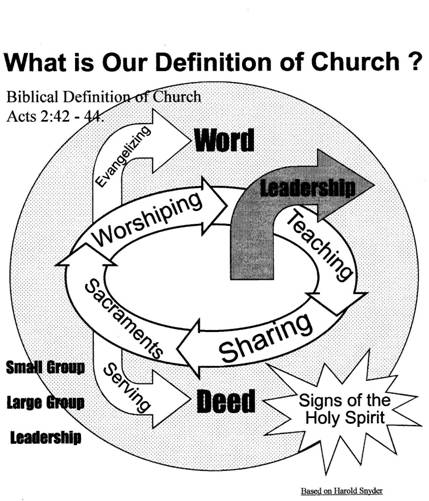

Howard Snyder is one of the foremost evangelical theologians to write on ecclesiology of the last century. He identifies the following structural elements of the Jerusalem church.

Traditionally these elements have clustered around theologies of Koinonia, Kerygma, and Diakonia.

Difficulties with Traditional Structuralist Views

In the context of Christendom in Europe, the church became established and central in nearly every village. Evangelistic momentum was lost in institutionalization.

The first difficulty in the unevangelized postmodern, Hindu, Buddhist or secular worlds is the institutionalisation of such structures into static pastoral structures in post-revival phases. The opposite dynamic is no institutionalisation as in the Jesus Movement in the US, who then become subsumed into denominational structures. Too rapid or too much institutionalisation leads to lack of spiritual freedom, corrupted theologies, loss of morality, and abuses of power. Too little leads to loss of faith, loss of movement dynamics.

The second difficulty has to do with perennial abuses of wealth in paying clergy and creating large buildings. There are sectors of the church that refuse paid pastoral roles (Bakt Singh, Jesus Movement in China, Brethren), believing that lay leadership precludes such abuse.

The third difficulty is that both institutionalization, power and wealth lead to moral corruption.

Extreme reactions to each of these issues (no buildings, no paid pastors, no institutionalisation) is probably as much a hindrance as the issues themselves, resulting in institutionalization of another kind. Instead of wise management of resources that facilitate the flow of revival and expansion of the church, the freeing of leaders to give time to ministry along with commitments to humility and simplicity of lifestyle by leaders seems more akin to Jesus' approach.

The Quest for Missional Ecclesial Structures

-

If Jesus' apostolic structure and the pastoral early church structures were quite different and Jesus made no mention of what structures were to be, what did he focus on? Structurally he was a brilliant manager, creating the structure of values, commitment, teamwork, with brilliant training, delegation, and campaigns (see the Training of the Twelve by A. B. Bruce or Coleman, R. E. (1993). The Master Plan of Evangelism. Grand Rapids, MI, Revellbooks). But he did not lay down a structure for "church"

There is a lot of attention given to the missional church, seeking to mould the pastoral into this missional mode. The difficulty of the missional church concept is that many in churches are struggling with horrific issues, and need care. Attempts to move pastoral structures into high commitment modes may destroy those with such needs in the name of growth (ambition?). Again a wiser approach is one of balance, of moving people at appropriate speeds step by step from institutional and static modes to fruit-bearing modes.

An alternative is to see there are two structures in redemptive history

The Quest for mDNA (Hirsch 2006)

A wiser approach is to go back to core values rather than structural definitions. For Jesus' focus of teaching was not on structure but on preaching high level values, ideas, vision, and on relationships, values, and the impartation of Spirituality. What were these values and impartation of the Spirit central to discipleship, central to his small group development? These were laid out in the spirituality of the Sermon on the Mount.

From implementing his values with small groups, comes transformation of lives, then impact on webs of relationships, then supplemented by teaching as to their implications, cultural values, then impact on societal structures.

The starting point for this sociological structuring of love then revolves around relationship, extended family, community, and core in that is hospitality

In other words, the less we formally tried to be church, the more we were able to link up with people and their issues and struggles. This occurred particularly in the practice of hospitality in our homes. people came to faith in Christ and developed commitments and discipleship not because they were formally evangelised or ministered to. This took place instead in the midst of friendship building, sharing life together and involvement in common duties of cooking, house cleaning, fun nights, talking and opening our lives to one another. This kind of lifestyle had the mark of reality and the ring of authenticity. Church, on the other hand, seemed formal or inauthentic. Her life was shared, while in the Sunday experience of church, certain religious ceremonies predominated.

From Communities to Congregations

All of the above can function well within extended family and multi-family clusters, or within clusters of specific needy groups, such as the Mongrel Mob, or with a 12 step group.

But what is needed at the next level of growth? What is the role of the Congregation? And from congregation to formalised church, what is the necessity of institutionalisation? For what purposes?

With the larger size group comes complexity of organisation, administration, staffing, funding, patterns of event, programs. Do you want that? Are they necessary?

A range of answers develop. An apostolic leader needs to have these answers defined clearly in his mind.

There are some like the Navigators who have opted simply to form small groups throughout society that study core values and disciple each other, They do not hassle with the congregational structure. But they have very clear leadership of the networks of cells, and there are large yearly conferences that affirm their core values, along with periodic Friday night gatherings of all the disciples in a city or a ministry. So they have large group dynamics but stripped of ritual, stripped of "the cult" (what anthrolopogists define as the rituals of religions; patterns of worship, patterns of prayer, liturgy, the robes, the candles, the religious symbols of power, the traditions) (Peterson, J. (1992). Church Without Walls: Moving Beyond Traditional Boundaries. Colorado Springs, NavPress. ).

They have all the characteristics of a religious movement, according to Gerlach and Hine’s study on movements (1970:xvii):

* face-to-face

recruiting

* personal commitment

* multi-cellular small-group structures

* an ideology which codifies values and goals

* opposition by existing power structures.

But they do not have churches, worship, liturgy, baptism, Lords supper, robes... On the other hand they would not exist if others did not have these things.

YWAM has similarly chosen a missional structure, where the larger group gatherings are ad hoc according to need for envisioning, or celebration or sustaining movment momentum.

Covenanted Communities

Critical to the expansion of small groups and the formation of congregations is the development of a core team or covenanted community. (See presentation on four seasons). Critical in this are skills in building momentum, team recruitment, and team building.

How Culture Determines Churchplanting Outcomes

Within 100 years after the Norman invasion of 1066, eleven hundred churches were built across England, copying the Norman style of church architecture, developed over the previous 1000 years in Europe. To this day, this defines "church" in England. WEC missionaries went to Uganda, "living by faith", trusting God for finances, and preaching and forming small churches. Today thousands of Ugandan Pentecostal pastors live "by faith" trusting God and going out preaching, leading small congregations as a result. In the high level marketing, and organising context of the United States, charismatic leaders can go out and recruit members form among the thousands of the 64% who attend church, resulting in churches of several thousand within a few years - thus mega-churches have formed, such as John Wimber's Vineyard in Southern California. In the first two cases imported models determined the church structures. In the latter cultural values determined it. Is it right? wrong? or is it just reality?

Elsewhere, I have identified several streams in the Auckland, New Zealand context.

1. Fundamentalism: Secure Haven in a Chaotic World

We now examine this morphing phenomenon. Harvey Cox’s premise is that in the postmodern post-secular context, religions (whether Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism) have all re-emerged in two forms, fundamentalism and experientialism. Both provide coherence where secularism has failed to provide a “culturally plausible response” (Cox, 1995:300-301).

Fundamentalism provides certainty in cultures that are increasingly incoherent mosaics of unconnected values, ideas and relationships (Ammerman, 1987: 192). It includes claims of absolute religious truth in the face of the societal disintegration inherent in secularism. On the negative side:

Fundamentalism

is not a retrieval of the religious tradition at all, but a distortion of it. The

fundamentalist voice speaks to us not of the wisdom of the past but of a

desperate attempt to fend off modernity by using modernity’s weapons (Cox, 1995:303).

In

2. Expanding Experiential Religion

The alternative experiential, storytelling, mystical style of religion requires less defined boundaries (i.e., works with centred sets rather than bounded sets). It can pull component truths from multiple sources, integrating and reintegrating them into new formulations. With their emphasis on the God who breaks in and on listening to the voice of that God, the charismatic movement and Pentecostalism place great emphasis on intuitive thinking. This leads to significant development of worship, music and creative arts. It also stimulates highly adaptive leadership styles — an essential element in modern urban church leadership (Hall, c1985).

Paralleling the cultural shift from rationalist anti-supernaturalism to informal supernaturalism, the religious shift appears to be from rational systematic theology and formal religion of the mainline churches to the informal supernatural religion of the charismatics and Pentecostals. Some term it a third reformation, focusing on the move from formal religion to the relational small group experience of much charismatic and Pentecostal Christianity (Neighbour, 1988; 1995). Significant differences appear in the underlying assumptions of these two movements however. Pentecostalism perceives an abrupt break with past Christian tradition. Charismatic Evangelicalism affirms the history of the church. The difference is highlighted by Smidt and leads to one of the dynamics of renewal.

Renewal

movements — that is movements that seek to make something old, new again —

generally seek to re-appropriate their particular roots and traditions. Consequently,

it would not be surprising if the Catholic renewal movement were to become more

‘Catholic’ than ‘ecumenical’ (Smidt, Kellstedt, Green, & Guth, 1999:125).

Charismatic

renewal seeking to renew, in many ways looks back. This ultimately diffuses its

strength as a movement. Pentecostalism, emphasizing discontinuity with the

past, can only look forward. It is not surprising, that 30 years after the

birthing of the charismatic renewal in

But there has been a levelling off of

this growth. Robin Gill, from 20 years

of analysis of church attendances in the

Our 'kingdom growth' typically runs at 8-10% - this is the number of people added to our churches each year through salvation/baptism etc. Since 1998 (when we first started recording it), it has ranged between 7.2% & 10.6%.

But the backdoor is also significant for these newer churches:

Overall,

we typically see 20-30% join/leave our churches each year. (In good years a greater percentage remain. In bad years those

joining and those leaving are about the same percentage).

3. Apostolic Mega-Churches

Church growth expert Wagner, speaks of the necessity of new wineskins as an outgrowth of charismatic experientialism, viewing new apostolic-led mega-churches as the probable post-denominational future (1999). These relate more to each other than to their own denominations (often being as large as their denomination). His definition of apostolic-led is problematic, but identifies the essential evangelising value of these churches. I have little doubt about their expansion as a reflection on the sociology of institutionalising religion, when I travel as a participant-observer from city to city. On the other hand, while such churches provide excellent structure, affirming and marketing revival as a significant theme, I suggest that this style of church violates many aspects of revival discussed in the following chapters. The centralising of human power and control, the emphasis on success and prosperity as against brokenness, confession and servanthood that mark revival, would indicate that their growth is not necessarily a sign of ongoing revival, but of social change and at times of post-revival control structures Peter Wagner and the church growth school believe that such centralised growth is a sign of God’s blessing. German church growth expert, Christian Schwartz has combated this in the genesis of the natural church growth movement (1996).

The Expansion of Revival Movements

Beyond these principles of revival, expansion of the concept of “groups” in the definition requires both theological and sociological development of a “revival movement” theory. Among the diverse definitions available, Snyder defines “a renewal movement” as,

a sociologically and theologically definable religious resurgence which arises and remains within, or in continuity with, historic Christianity and which has a significant (potentially measurable) impact on the larger church in terms of number of adherents, intensity of belief and commitment and/or the creation or revitalization of institutional expressions of the church (1989/1997:34).

This is a very church-focused definition. Orr uses the term “evangelical awakenings”.[10] Lovelace comments that “revival,” “renewal” and “awakening,” “usually are used synonymously for broad-scale movements of the Holy Spirit’s work in renewing spiritual vitality in the church and in fostering its expansion in mission and evangelism” (1979: 21).

The repetition of revival dynamics is foundational to the rapid expansion of Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism, both of which can be perceived as the fruit of series of revival movements occurring across multiple cultures, with overlapping timeframes. The literature on revival themes that grows from interpreting these movements is extensive and expanding.[11]

Cultural Structure and Growth beyond Cells and Congregations

Two contributory and popular missiological terms are helpful. People groups is a sociological concept used in missiology by Donald McGavran (1970:223ff), the founder of church growth theory and marketed by Ralph Winters globally.[12] Flow of ideas (or the transmission of the power of the Spirit) within such groups is rapid, through webs of relational ties until it meets a racial, ethnic, class or other barrier (a web movement).[13] There is usually a multiplier effect that is often graphed to show an exponential spread of the gospel as revival dynamics expand – until they hit barriers of war, famine, other catastrophe, or heresy that curtail expansion.

The idea of web movements, can be

utilised to understand revival movements within the Scriptures. We can consider

the structure of Acts as built around several web movements – the

multiplication within the

The Quest for Missional Success in the Midst of Pastoral Realities

The quest for some, is how to move the existing church from its preoccupation with institutional and cultic issues to people concerns. For others, it is what blueprint do we have for developing new churches with mDNA?

I’ll let Eugene Peterson have the last word about traditional church,

The biblical fact is that there are no successful churches. There are,

instead, communities of sinners, gathered before God week after week in

towns and villages all over the world. The Holy Spirit gathers them and does his

work in them. In these communities of sinners, one of the sinners is called pastor and given a designated responsibility in the community.

The pastor's responsibility is to keep the community attentive to God. It is this responsibility that is being abandoned in spades.

[10] Language has now moved on and a cursory look at the web shows the word “awakening” now commonly used for those awakening into spiritist experiences. For this reason, I have not used it.

[11]Analyses of the revivals in Europe and the

[12] A People Group is “a significantly large grouping of individuals who perceive themselves to have a common affinity for one another because of their shared language, religion, ethnicity, residence, occupation, class or caste, situation, etc., or combinations of these.” For evangelistic purposes, it is “the largest group within which the gospel can spread as a churchplanting movement without encountering barriers of understanding or acceptance” (Winter & Koch, 1999: 514).

[13] See Tippett, (1971:40-59, 198-220) for example, and his figures on the expansion of Christianity among Maori in the 19th century.

References

Hirsch, A. (2006). The Forgotten Ways. Grand Rapids, Baker.

Learning Outcomes

1. Students will be able to contrast models of church and justify their choice of a particular style of church as the outcome of their Work.

2. Students will be able to reference most recent and critical literature of the nature of the church